STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES OF THE EXTERNAL EXAMINER MECHANISM

This is the text of a paper I presented at an FIE conference in 2005. It discusses the UK’s external examiner system that provides a mechanism to enforce comparability of standards across UK universities at the undergraduate and Master’s levels.

Alan Clements

Abstract – There are many differences between British and US universities. Nowhere is the difference greater than in the way in which students are assessed. US professors have considerable autonomy in how they set and grade an exam. UK universities implement a complex process that interlocks universities to create a common procedural standard across the country. A UK academic sets an exam and produces specimen solutions plus a marking scheme that are sent to a senior academic, the external examiner, in another university. The external examiner comments on the suitability of the exam and the teacher setting the exam should modify the paper if requested. When students take the exam, the external examiner samples their work and comments on the results. The external examiner is responsible for academic quality control. This paper describes the UK’s external examiner system and looks at the strengths and weaknesses of the mechanism and its influence on higher education in the UK.

Terminology 1

Educational terminology varies from country to country. Here, we use the term course

to mean a program of studies leading to a degree. The term unit (also called module)

is a unit of assessment such as computer architecture or data structures. In the

USA the term course is used where someone in the UK would use unit or module. Higher

education refers to courses leading to an under-

The term professor is used differently in the USA and the UK. In the UK most academics are lecturers and the term professor is reserved for distinguished academics. In this paper I use the terms teacher to avoid confusion.

Background

The higher education system in England consists of about 100 universities that are centrally funded by an organization called HEFCE (Higher Education Funding Council for England). With few exceptions, universities in the UK belong to the state sector that is characterized by a common approach to quality control and standards.

Although universities in the UK are state-

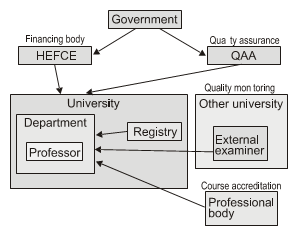

Figure 1 describes the organization of England’s higher education and the position of a university within it. Central government does not directly interact with universities. Government funds HEFCE which allocates funding to universities [1]. A separate public body, the QAA (Quality Assurance Agency), promotes and maintains standards in higher education. The QAA’s mission is “to safeguard the public interest in sound standards of higher education qualifications and to encourage continuous improvement in the management of the quality of higher education” [2].

FIGURE 1

Structure of Higher Education in the UK

Within a university, the registry is responsible for implementing academic rules concerning student progression. Progression implies the ability to move on to the next stage of a course. In the UK a cohort of students starts together in their first year and normally progresses in step to their final year. It would be rare for a student to take units at different levels in the same academic year (unlike the USA where students can take several units at different academic levels in the same academic year).

An important component of Figure 1 is the external examiner, who is normally a senior academic at another university responsible for ensuring that the academic standards of a particular course are maintained. An external examiner can sometimes come from industry. Figure 1 also refers to a professional body; this is a separate body with no formal status within the university but which has the power to accredit a degree course. In the UK this body might be the British Computer Society or the IEE.

Terminology 2

Examination boards have their own terminology. A student is said to be condoned if their result in a module is a marginal failure but can be treated as a pass (to be condoned they have to perform well on average across other modules).

A student is referred if they have failed a module and must retake it to progress. Referred students take a special resit examination.

A student is deferred if they fail a module but have mitigating circumstances such as illness. In this case the student also takes a resit exam but is considered to be taking it for the first time. Consequently, if a deferred student fails the resit they are referred and can take a second resit.

A core module is a unit considered essential to the degree program. A student must pass all core modules to receive their award. If a core module is failed, the student must either leave the university or switch to a different course (i.e., another degree program).

Organization of a Course

A department has a course board that is responsible for the organization of a course;

its curriculum, staffing, resourcing and teaching. Students are assessed by regular

pieces of work (continuous assessment) or by an end-

Exam results in the UK are not awarded in isolation without considering other students and the units they study. All student results are issued by exam boards. Indeed, if a teacher gives a student 60% in an exam and tells the student the result before the exam board has met, that teacher could be sacked for committing an act of gross professional misconduct.

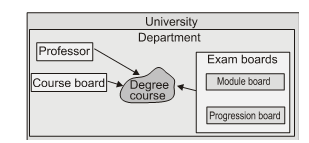

Figure 2 shows the relationship between a course and the boards within a university department that implement modular courses in which students take individual units or modules that comprise a degree course. These boards are:

- Course board – this is responsible for the regulations concerning a degree course and the curricula of the individual units

- Exam board – this controls the assessment process

- Module board – this component of the exam board is responsible for the way in which units carry out assessment

- Progression board – this component of the exam board is responsible for the progress of individual students taking the course.

At a module board, a group of units are discussed by the entire faculty involved

in their teaching, tutoring and examining. For example, a module board may comprise

units in computer architecture, operating systems, and computer networks across degree

courses in computer science, information technology and software engineering. Those

responsible for teaching a unit report on their unit at the module board. For example,

a module leader would report whether the assessment results were as expected, and

describe any problems that arose during the running of the unit. The module board

provides a report-

FIGURE 2

Organization within the department

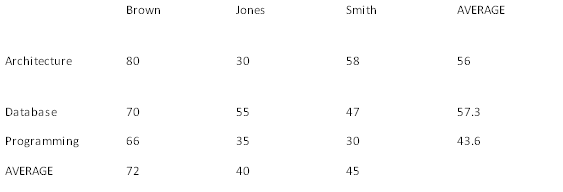

At the module board, individual students are not discussed. Figure 3 illustrates

the two-

FIGURE 3

Student and Unit Results

The module board has the power to scale assessment results to deal with units where the board thinks that the results do not accurately reflect the ability of the class. The module board is also responsible for determining the nature of any referrals (repeat exams) to be taken by a student who fail units. Once results have been ratified by the module board, they are fixed and cannot be further modified.

The progression board meets after the module board. Progression boards are arranged by course (e.g., BSc in software engineering or BSc in computer science). Individual students are considered at the progression board, using their unit results passed on from the appropriate module board. In Figure 3 the progression board would be interested only in the marks achieved by Brown, Smith and Jones. At the progression board, individual units are not discussed because they have been dealt with by the module board.

The progression board determines how each student is to progress. If a student has passed all their units, there is no problem. If a student fails one or more units, they are discussed by the progression board to determine what steps must be taken. Some marginal fails can be condoned. Sometimes a unit must be retaken. However, if a core unit is failed it may be necessary for the student to switch to another course that doesn’t have the same core unit. A progression board has a chair, a secretary, a representative from the registry and usually two external examiners (who are responsible for ensuring that rules are correctly applied and appropriate procedures followed).

The External Examiner

An external examiner is appointed to monitor a course. External examiners are normally

senior academics who are paid a modest honorarium for their work during their fixed-

The external examiner takes part in the development of a course as an advisor and is consulted whenever rules are changed. The external examiner’s principal role is in quality control and the monitoring of the exam procedure.

A professor in the USA may create an exam paper on Monday, give it to the students on Tuesday, and grade it on Wednesday. In an English university, a teacher sets an exam with a marking scheme that provides sample answers together and an indication of how the marks are to be allocated. This exam is handed in to the secretary responsible for exams. The exam office sends the exam and its marking scheme to another member of the faculty for checking. This teacher returns the exam with corrections and suggestions and the person who set the exam creates a new version.

Having been checked internally, the exam paper is now sent to the external examiner who looks at the paper from the point of view of accuracy, conformity to the curriculum and quality. The external examiner would, for example, consider whether the assessment examines all parts of the unit and whether it is capable of discriminating between poor, good and very good students. The external examiner the returns the exam paper with comments and suggestions. These are passed to the unit leader who is expected to make the appropriate changes.

Clearly, such a long and involved process of setting an exam means that it is difficult

to fine-

The role of the external examiner does not end with the checking of exams. After the students have taken the exam, the external examiner visits the university and attends the unit and progress boards. The external examiner has the right to comment on any aspect of the department’s work and assessment procedures. The external examiner scrutinizes work that has been graded (on a sampling basis) and may even interview students and staff. The external examiner signs final pass lists to validate them.

After the exam boards have met, the external examiner returns to his or her own university and writes a report. This report is sent to the other university’s registry as well as to the head of department. The department is expected to implement any suggestions made by the external examiner and to report back to them. Ignoring an external examiner’s comments is not an option.

The External Examiner’s Report

Most universities provide the external examiner with a pro-

The following material summarizes the type of questions asked of external examiners in their final report. This material is taken largely from the University of Bristol’s guidelines [3]. In order to ensure that an examiner’s report is timely, the external examiner’s fee and expenses are sometime not paid until the report has been received. The external examiner’s comments consist of two parts; those that are open for publication and those that are private to the institution and are not circulated publicly. Typical questions asked of the external examiner are:

- Are the standards set appropriate for the awards (by reference to published national subject benchmarks and institutional program specification)?

- Are the standards of student performance comparable with the standards of similar programs in other UK higher education institutions with which the examiner is familiar?

- Are the University's processes for assessment and the determination of awards sound and fairly conducted?

- Please summarize the key characteristics of the program that you consider significant, and identify any notable strengths and distinctive or innovative program elements.

- Please comment on the extent to which the assessment methods test the program or unit learning outcomes.

- Please comment on the appropriateness of examination papers and other forms of assessment.

- Please comment on your overall impressions of the assessment process, including department marking scheme(s), faculty guidelines, and administration of the process.

- Please comment on the general quality of the candidates' work and how it compares with their level of study.

- Please comment on any good practice encountered for any aspect of the unit examined and any areas that should be strengthened or risks which should be addressed in order to maintain confidence in standards on the program.

- Please comment on the program structure and content, including the suitability of program and unit aims and learning outcomes and the extent to which they were achieved.

- Please comment on

- the range and suitability of teaching and learning methods experienced by students

- examples of research informed learning and teaching and student achievement

- Staff/faculty expertise

- the level of learning resources available in the subject you examined (including the standard of accommodation and equipment for leaning and teaching)

- adequate accessibility for all students (including disabled students) to learning and teaching resources.

An external examiner in their final year of office may also be asked to provide a retrospective comment including their views on the way in which teaching and assessment have changed..

As these questions demonstrate, the external examiner’s scope is very broad and can encompass the whole of a student’s learning experience. Criticisms made by the external examiner are normally treated most seriously and must be responded to.

External Examining in Practice

Written and Unwritten Reports

I have described the formal student assessment procedure in England. Now I comment on the mechanism from the point of view of a teacher whose own work is viewed by external examiners and who is an external examiner himself.

A good external examiner is a political animal. A critical report from an external examiner can have a devastating effect on a department – not least in terms of faculty morale. I’ve seen faculty reduced to near apoplexy by a critical comment from an external examiner in an exam board; for example, an external examiner may comment that a particular faculty member achieved a low standard deviation in their exam and, therefore, the exam failed to discriminate adequately between student abilities.

Because a negative report from an external examiner can have such a strong effect

on a department, you can use the mere threat of a negative comment to achieve the

desired correction. For example, suppose a particular teacher has a propensity to

set exam questions that are too textbook-

On one occasion I had criticized some aspect of a department’s exam procedures. I

discussed this with the head of department before the exam board and he agreed fully

with me. Indeed, he suggested that I mention it to the faculty at the exam board.

I did discuss the failings in the process at the exam board and the head of department

jumped down my throat, defended his faculty and criticized me. I was rather shocked

by the head’s about-

Strengths and Weaknesses

- At its best, the external examiner mechanism:

- ensures that standards between universities are broadly comparable

- creates a society-

wide confidence in the examination process - provides teachers with a mentor from an external university

- provides a means of ensuring quality at the micro level; that is, at the level of the individual classroom teacher

- provides a means of sharing best-

practice between universities.

The following anecdote demonstrates an interesting side-

In Place of Strife

Although there is a module and progression board for each semester of a student’s course, the key board is the final progression board which is called the awards board because it awards degrees; in particular, it awards categories of degree (see Terminology 3).

Terminology 3

In the UK undergraduate degrees are classified in five bands. These are:

First class. This is the highest level of degree and students are required to get

an average above 70%. A first-

Upper second class. This is also called a two-

Lower-

Third class. Students with a 2(1) or a 2(2) are said to have a ‘good honors degree’. Students do not want to achieve a third class degree.

Pass. This is an unclassified degree and is really just above the fail-

Degree classification is partially automatic because a formula relates a student’s final classification to their average results during the final two years of their course. The awards board has the discretion to change a classification that is close to the boundary between two degree categories. For example, although a student may not have achieved sufficient credit to achieve a first class degree, his or her teachers may feel that the results do not truly reflect the student’s actual ability.

The board debates the student and each of his or her teachers states what they feel about the classification. The external examiner is then given the opportunity to comment on the case. Often the external examiner will say “You know the student – you decide”. Sometimes the external examiner will give strong guidance to the board by stating that they have made a good case for promoting the student.

A considerable amount of strife can be generated at an awards board when a teacher strongly champions their student but their colleagues do not accept a recommendation for a change in the classification of the degree. This situation often arises where a student who is 1% below the boundary is not elevated whereas a student 2% below the boundary is elevated. The reason for this apparent anomaly is usually that the student 2% below the boundary has underperformed, whereas the student closer to the boundary is deemed to have been treated appropriately.

A progression board also deals with cases of academic misconduct. The investigation of such cases takes place outside the board and the findings are passed to the board. The board’s role is only to take into account the misconduct when determining the student’s progression.

As an external examiner, I have been involved in cases where the board was undecided about the nature of the penalty to be applied in a case of, for example, plagiarism. Some board members suggested a modest penalty such as retaking of exams and others suggested a more draconian penalty such as a reduction in the classification of the degree. In this case the debate was heated and I was asked for my advice. Because all students had been told of the consequence of plagiarism and because the plagiarism was in the student’s final year capstone project, I came down on the side of those opting for the more severe punishment.

Side Effects of the External Examiner Mechanism

The negative side of the external examiner mechanism is the distorting effect it has on higher education. Teachers know that their work will be scrutinized by the external examiner and commented on publicly if the work is found wanting. Suppose a particular class is rather weak – it happens because of statistical fluctuations in the ability and personalities of students in a class. The average mark achieved by such a class might be lower than usual. A teacher who is worried about being criticized at the module board and the external examiner might be tempted to set apparently difficult questions and then coach the students by going over very similar problems in class.

In attempting to satisfy the external examiner, the teacher distorts the education and assessment process by modifying the teaching to suit the perceived needs of the external examiner rather than the real needs of the student.

Another negative effect of the external examiner system is that it limits the rate at which educational change can take place and makes it harder to introduce substantial innovation. For example, suppose a class is not putting sufficient effort into their work. The teacher cannot simply introduce an extra test or exam – a change in the assessment mechanism would have to be referred back to the course board. It is possible, of course, for teachers to introduce an optional informal test. However, the students know that such a test cannot be used to determine the outcome of the course and, therefore, they know that they do not have to participate if they don’t want to.

The role of external examiner cannot be discussed in isolation from the politics

and economics of higher education in the UK. In the 1960s only a tiny elite (less

than 10% of the population) received higher education; all tuition fees were free

and most students received a modest wage (i.e., grant) while attending university.

Entrance was by competitive exam and the drop-

What are the implications of these changes for the present assessment system? Is it possible for the external examiner system to be maintained in circumstances where there is a wider range in the characteristics of universities than there was a generation ago? Can external examiners maintain academic parity between Russell Group universities (the UK equivalent of the Ivy League) and provincial universities with a much higher percentage of less able or less motivated students? I fear that the UK’s external examination mechanism may drift into a world where procedure is everything and reality is ignored; for example, an examiner was asked (as part of their report to the module board) to indicate which of the unit’s objectives had been covered by the exam paper. The examiner said that it would take some time to match the questions against the unit’s objectives. He was told by a colleague, “Oh, just invent the numbers – there’s no way they (i.e., the external examiner) can check everyone’s exams against objectives.

Conclusions

Although UK examination procedures put restraints on academics, they hold the teacher to the promise delivered to students taking the course. The assessment procedures guarantee that students will be taught what is described by the course documentation and they will be taught by teachers who are expected to teach to a standard that is respected nationally. Moreover, students can expect fairness and know that their work is monitored by all faculty and reviewed by the external examiner. In my experience external examiners perform their task fairly and conscientiously; after all, an external examiner is just a colleague from another university and not part of management or the bureaucracy.

The external examiner mechanism cannot be viewed in isolation from the entire system. Increasing pressure to ensure quality is generating cynicism amongst some UK academics. There is a feeling that the system is interested in process rather than outcome, and that you are being forced into a situation where teaching and assessment has become a matter of satisfying the external examiner and the quality assurance bodies, rather than actually educating the students.

I believe that the external examiner mechanism benefits UK education by promulgating good educational practice and by eliminating bad practice. However, those who control the quality assurance mechanisms in the UK must appreciate that increasing quality control may lead to a diminution of the actual quality at a time when the number of students in higher education is increasing dramatically.

References

[1] Higher Education Funding Council for England, http://www.hefce.ac.uk

[2] Quality Assurance Agency, www.qaa.ac.uk

[3] Bristol university, “Guidelines for external examiners”, http://www.bris.ac.uk/exams/forms/extreporttemplate.doc

[4] Universities for the North East, “Student retention, support and widening participation in the North East of England”, http://www.unis4ne.ac.uk/unew/ProjectsAdditionalFiles/wp/Retention_report.pdf, March 2002.

[5] The external examiner: how did we get here? Mike Cuthbert, University College Northampton http://www.ukcle.ac.uk/events/cuthbert.html